As co-teachers and instructional partners, school librarians focus on collaborative opportunities with individual or teams of educators within a school community. Many school districts have been providing professional development for educators by establishing Professional Learning Communities (PLC). The PLC is a vehicle for collaborative planning and decision making that focuses on improving student learning. To be successful participants, educators need training to understand the process for and commitment to collaboration that builds the collective capacity of a school system. An effective PLC can change attitudes and transform teaching and learning in a powerful way.

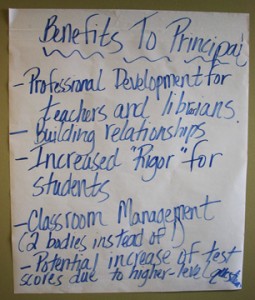

School librarians are positioned to take leadership roles in PLCs, and should advocate for a place at the table. Having honed a variety of collaboration skills of various levels, school librarians are familiar with setting goals, timelines, assessments, formulating projects, and are adept at analyzing data. There are many configurations for PLC teams, and the school librarian should have a pivotal role in content areas. Unfortunately, in many districts, the PLC teams may not integrate the school librarian into content or grade level groups. Many times the PLCs are set to meet during the scheduled time for a class visit to the library/media center when the librarian is expected to supervise the class. That prevents meaningful participation, and limits the expertise and knowledge that the librarian can share with the group.

Stepping into a leadership role means that the school librarian needs to be proactive and stay ahead of the curve. Find out what is happening in your district or school. What are the initiatives? What are the goals for educators and student learning? What curriculum changes are proposed? Be ready to explain to administrators, teachers, parents, community members, and students how the school library program and resources will benefit the transformation of learning. You are the expert, the information specialist, and can facilitate learning for all stakeholders.

If you want to realize your own capacity as an educational leader, I recommend two readings that have influenced my thinking recently. One was an article in May/June 2013 issue of Knowledge Quest, “The Make-Good Mission.” Michael Edson, the Smithsonian’s director of web and new media strategy, talks about the possibilities for the school library as a place for meeting the challenges of “scope, scale, and speed” presented by information in present day. We simply can’t continue to do things the way we have done them in the past. Organizations have to change from within, not top down. We all have the capacity to contribute, not just receive information.

Change from within is one of the messages also in Leaders of Learning: How District, School, and Classroom Leaders Improve Student Achievement (DuFour and Marzano, 2011). Two leaders in organizational systems and education explore how change and transformation can come about using the collective expertise of all stakeholders. DuFour shares how PLC teams that are created and supported by district administrators and principals, can bring about improvements in student learning. The training and support is imperative to make a successful outcome for all. Collaboration skills have to be learned and the authors offer a blueprint. Marzano clarifies how to establish what is important for students to learn and how to assess their learning.

At the AASL Conference in November 2013, there will be sessions that focus on leadership roles and require specific collaboration skills. Come to conference and gather more ideas to add to your leadership/advocacy tool kit!

Resources:

DuFour, Richard and Robert Marzano. 2011. Leaders of learning: How district, school, and classroom leaders improve student achievement. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Edson, Michael. 2013. The Make-good mission: Evaluating and embracing new possibilities for discovery and innovation in school libraries. Knowledge Quest 41 (5): 12-18.

Photo: Microsoft clipart