I just heard from a student who is preparing to start her first year as an elementary school librarian. She’s been working all summer to create a welcoming space for her students and she wanted to know if there were any resource books I might recommend for library lessons. I remember wanting that book when I started out as well. But I never found it because ultimately the best lessons are those that you create yourself for your unique context with your unique stamp of creativity. And they are created in response to the needs of your students and teachers and discovered in a collaboration with the school community.

I just heard from a student who is preparing to start her first year as an elementary school librarian. She’s been working all summer to create a welcoming space for her students and she wanted to know if there were any resource books I might recommend for library lessons. I remember wanting that book when I started out as well. But I never found it because ultimately the best lessons are those that you create yourself for your unique context with your unique stamp of creativity. And they are created in response to the needs of your students and teachers and discovered in a collaboration with the school community.

But where do you start?

Try to find out what’s happening in classrooms/grade levels so you aren’t teaching skills in a vacuum. For example, I did a reading interest survey every year with 3rd grade but then presented the findings as large graphs that I used for lessons related to their math curriculum and then posted outside the library for everyone to see. I usually asked teachers what they were doing in science or social studies because those were easy content to grab on to. Then I might ask what they were teaching in reading or writing and find a way to integrate those with library resources/skills. So when I learned that second grade was studying voting in social studies and using literature for writing models I introduced the Jane Yolen, How Do Dinosaurs... series and we wrote a class book about “How Do Dinosaurs Vote?”

It helps if you have some theme that you pull through the lessons and the year. So one year I was asked to focus on integrating math; another year the focus was science – in these cases the principal or the school improvement plan allowed me to see what was a schoolwide focus that I could work with. Or decide that you will make this the year of poetry or the year of working with video and find ways to integrate those with as much content and lessons as possible. Then you can stand up in a faculty meeting and say “This year the library focus will be on poetry and I invite you to plan lessons with me that integrate poetry. I’m sure I can find a poem for anything you are teaching: math, science, social studies. And you can expect to find poetry popping up in unusual places like the morning announcements, the cafeteria or the bus line.” You’ve provided an invitation and a challenge.

What are teachers being told they need to do more of this year? — find out how you can help or even lead any initiative. One year teachers were introduced to thinking maps so I was modeling those with every library lesson. I attended any staff development required of my teachers and then tried to integrate what they were told to do in their classrooms with what I was doing in the library. When I was planning with teachers this willingness to support them in new initiatives was greatly appreciated.

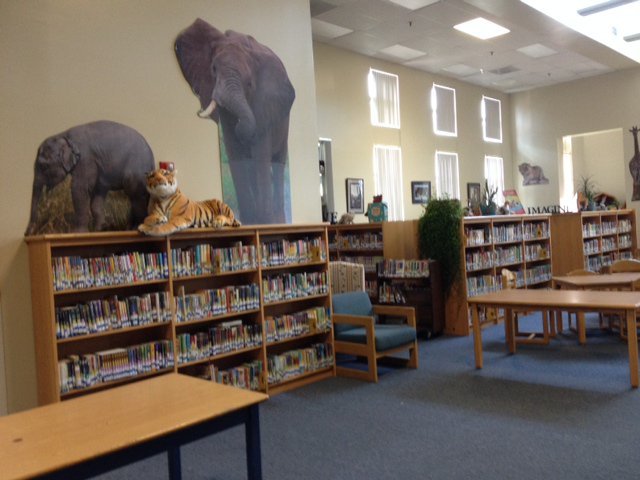

Use what you have – this may seem obvious – but look around to see what kinds of resources are unique and underutilized – online databases, ebooks, whiteboard, old sewing machines, puppets, a collection of magazines…

One year I built my lessons around my state’s children’s book award list. I noticed that a lot of the books had some relationship to math concepts and I was able to integrate literature with mathematics in collaborative lessons. Then we were able to participate in voting for the award.

Today I would be looking around for lesson ideas on Pinterest or Livebinder and curating my own collection of ideas. Find colleagues who are willing to share ideas and don’t be afraid, as one of my mentors told me to “beg, borrow and steal” ideas but combine them with local needs and resources to spin your own particular kind of magic.

Yolen, Jane (2000). How do dinosaurs say goodnight? Scholastic. Find this book and others in the series at http://www.scholastic.com/titles/dinogoodnight/

Photo courtesy of Jessica Thompson (2014).

During the past two weeks I have attended the Virginia Association of School Librarians Conference and the AASL Bi-Annual Meeting in Hartford. In Hartford, I attended a pre-conference led by Audrey Church, Jody Howard, Judy Bivens, and Mona Kirby on

During the past two weeks I have attended the Virginia Association of School Librarians Conference and the AASL Bi-Annual Meeting in Hartford. In Hartford, I attended a pre-conference led by Audrey Church, Jody Howard, Judy Bivens, and Mona Kirby on